Language and communication have the power to shape how people become who they are in relation to each other. When we pay attention to how people speak and use their bodies in everyday interactions, we can learn a lot about their cultural values and power relations. In Vietnam, for example, hierarchy and sacrifice need not necessarily feel like exploitation and oppression, as they might in America. Rather, even before children learn to speak in Vietnam, they learn that hierarchy and hy sinh—translated as “sacrifice”—can be forms of care that involve what I call asymmetrical reciprocity. This means giving to each other, but not in symmetrical, equal ways: those with lower status (such as children) owe respect to those above them. But at the same time, those with higher status (such as parents, ancestors, and bosses) must yield to and provide for those below them.

To study this cultural alternative to a stereotypically American (capitalist, Christian) version of sacrifice and hierarchy, I spent over a year living with and visiting families in central Vietnam, using language socialization as a research method.

To study this cultural alternative to a stereotypically American (capitalist, Christian) version of sacrifice and hierarchy, I spent over a year living with and visiting families in central Vietnam, using language socialization as a research method.

Language socialization is an ethnographic approach that studies how different members of a community learn from and teach each other cultural ways of feeling, acting, and thinking through embodied communication. This approach reveals how, in what seem like simple, everyday routines like greeting older family members and neighbors with a slight bow, the Vietnamese cultural logic of sacrifice and hierarchy works in practice. This involves yielding to those with less power and paying respect to those with more. It works across levels and generations, instead of exclusively resulting in the exploitation of social “inferiors” by those above them.

Here’s an example. Ly, a 53-year-old, high-ranking official, has just come to visit her grandfather’s house for his annual death anniversary. Her grandfather, now an ancestor, died more than 50 years ago. The family’s eldest men are sitting and chatting in the front room, while younger women are in the kitchen, having worked all day to make specialty dishes to feast on and honor Ly’s ancestor.

Until this moment, I was used to seeing Ly graciously command people as a supervisor, loving mother, and elder sister. But as we entered the front room, she folded her hands on her chest and slightly bowed like a child, greeting the elderly men one by one. The other adult guests similarly stopped at the edge of the front room, folded their hands on their chests, and bowed slightly to greet the elders. Each used the appropriate kinship term (chào ông/bác/chú/cậu,“Greetings, Uncle!”) before entering the house to light incense for the ancestor and help set up the ritual feast.

Such feasts and greetings were times when descendants performed respect for their ancestors, while younger generations simultaneously displayed their gratitude and obedience not just to the deceased but also to their parents and grandparents. Prescribed by Vietnam’s Confucian and Buddhist heritage, where ancestors are at the top, followed by grandparents, then parents, and finally children at the bottom, these traditions emphasize relations of hierarchy within the family and throughout society. They assume that since grandparents and parents sacrifice so much raising their children, their children owe them no less care as they age.

This kin-based hierarchy is a cornerstone of filial piety, the idea that dominates in Vietnam and many other parts of Asia that children owe boundless, unrepayable gratitude to their parents and ancestors. Hy sinh (sacrifice) is related to filial piety, but it’s broader. Hy sinh includes fighting for your country in war, worshiping ancestors, and doing various caring acts for your fellow countrymen, friends, and, most of all, loved ones. Sacrifices could include not eating to make sure that loved ones have enough, holding your tongue to prevent a fight, or holding back tears once a loved one is ritually buried so their soul won’t be tormented by your calling it back. As I found, it leads those who are older, wealthier, or more powerful to yield to and treat with kindness those below them, while those at the bottom owe gratitude and respect to those above them.

But how do people learn hy sinh,and what sort of society and vision of justice do we have when they do? I observed how children learned hy sinh through language socialization but also how adults demonstrated care to those lower than them in the hierarchy. From this, we can see how hy sinh creates a vision of society in which hierarchy becomes equitable over time rather than immediately and symmetrically.

Let’s now focus on a language socialization instance I observed when 15-month-old Em and her mom were in their neighbor Minh’s yard. As I did every 4–6 weeks rotating among families, I filmed their ordinary interactions to learn about their language and cultural practices. That Sunday, I stood in the yard along with Minh’s wife Vi and 5-year-old son Kinh.

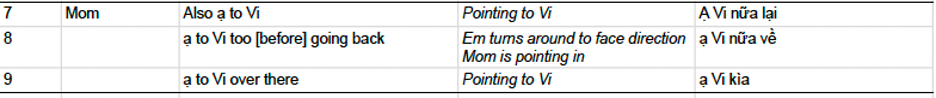

What I recorded and the transcript I produced (which provides notes on exact words, body language, and tone of voice) may seem trivial. In response to the adults’ commands, toddler Em at first bows correctly but then too low, as if bowing to a dead ancestor, instead of using a slight curtsey accompanied by the respect word, ạ. Mom scolds and corrects her, insisting that Em must bow the right way. We might not even notice these small instances of seeming child rebellion and adults’ insistent corrections. But when we pay attention even to just one minute of the transcript—from when Mom starts directing toddler Em to respectfully take leave of her elders until when Em vigorously waves and says “bye” to Kinh—we can see how this ordinary interaction is an important opportunity for Em to learn what’s culturally expected of her and for us to see how adults teach and practice hy sinh.

Let’s see how it unfolds. From the whole transcript, we see the adults are in power: they are the main speakers (vocalizing 18 of 23 lines, about 80%), and their utterances are mostly commands. From the start, Mom asserts her authority. In rapid succession, she utters a statement (“Enough, [let’s] go back”), asks a question she doesn’t really want answered (“Ready to go back?”), and immediately follows it with commands (“Perform respect [before we] go back” and “Perform respect to Minh [before we] go back [home]”). Neighbor Minh adds to Mom’s authority by repeating the command to Em but in a solicitous way that’s designed to show her how to do it (“Go ‘ạ,’ ‘ạ-ạ’”).

Vietnamese caregivers often assume that young language-learning children “don’t know anything” and constantly prompt toddlers to greet their elders by slightly bowing while saying a shortened version (ạ) of the respect word (dạ). They explain that frequent promptings and use of the short version make it easier for young children to learn (see Em at an even younger age being prompted and successfully greeting me with ạ and the slight bow). As children mature, they use dạ at the beginning of utterances addressed to their elders, without prompting, even in text or social media messages.

What happens next with Em? Even before Minh finishes showing-telling her, Em displays her understanding and agreement to play her part as a younger, respectful person: she bows her head and says “ạ” twice, elongating (stretching out) the vowel just like Minh had. Satisfied, Mom points to Vi and tells Em to greet her respectfully too.

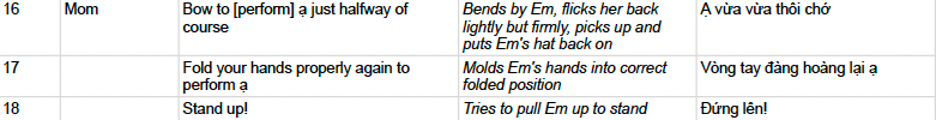

But this is where trouble begins: Em says “ạ” in the elongated way, as allowed and even expected, but she bends and bows very low, and almost falls, catching her balance with her hands. Mom initially laughs, but immediately also scolds Em (“Enough!”) as the toddler gets up. Mom steps towards Em, flicking her gently while instructing, “Go ạ” and steps back while instructing Em to correctly bow: “Fold your hands to perform ạ again.” Em repeats the same elongated utterance and low bow, and Mom again corrects her, both verbally and by flicking Em. Mom then picks up Em’s hat, places it back on the toddler’s head, and again instructs while molding Em’s hands into the correct folded position, after which she tries to pull Em up to stand and try again:

This sequence may at first seem to be a simple politeness routine, like when Americans expect their children to say “goodbye,” “please,” or “thank you.” But a closer look shows that it’s not just words that are important but also body postures that adults emphasize. Mom’s commands and physical corrections could seem harsh: she flicks, molds, and corrects her young daughter and uses “of course” to imply that Em should already know this. Mom’s tone, however, indicates humor, and her movements are gentle attempts to help Em.

This exemplifies the asymmetrical reciprocity and sacrifice that Em is learning. Even before knowing the words, Em is learning to associate specific postures with behaviors, emotions, and occasions. The deep bows that Em has seen her elders perform countless times when praying to the Buddha and to ancestors are not the type of bows that she must do when greeting her elders.

As the authority figure, Mom repeatedly corrects Em’s posture and bow, indicating that the toddler’s correct vocalizations are not enough. Yet Mom also yields after seeing the repeated mistake, saying, “Ok, stand up” and then directing Em to wave/say goodbye to Kinh. In short, Mom does not play the part of a tyrant. Instead, she insists on proper forms of respect, not prompting Em to use the correct honorific (respectful title) towards Kinh (anh, “older brother”) but rather the Viet-English bay bay (“bye bye”). Unlike the respectful Vietnamese ạ that must be accompanied with the slight bow, “bye,” as an English loanword without Vietnamese overtones, can be accompanied by as long and exaggerated a wave as Em clearly wants to perform.

This type of short interaction takes place often, usually without mistakes and corrections. Children and adults know their respective places in Vietnam’s hierarchical social system and treat each other accordingly. By paying attention to participants’ language socialization practices, we can see the cultural logic of Ly’s and Em’s bows. These similar but not identical acts signal the hierarchies among the different participants (toddlers and their elders, Ly or other adults and their elders, descendants and ancestors), where those with lower status must honor and respect those with higher status. Conversely, those with higher status yield to and kindly care for those honoring them. Both sides must sacrifice for each other by suppressing some desires and comforts for others’ sake; they do so in different and unequal but, as they believe, equitable ways over the life cycle, and this is their version of justice, based on hierarchy rather than equality.

The passage of time is key here: obligations even out over generations, instead of in immediate, quid-pro-quo relations (like paying and getting something in return right away). In age hierarchies, we see that statuses are dynamic rather than fixed: toddlers grow up to expect the honor they used to give, now from new toddlers. As adults, they are expected to marry and produce descendants for their ancestors, so that the cycle of sacrifice can continue—they take care of the younger generation and expect the younger generation to take care of them as they get old and long after they die. No violence is involved here, only asymmetrical reciprocity, learned through routine language socialization practices. While other hierarchies, like gender, might involve oppression, by paying attention to language socialization and asymmetrical reciprocity, we can better understand how hierarchy doesn’t have to only be exploitative but, in some instances, can produce equitable systems over time.