Pictured above: DLP student interns Drew Horsford and Jonathan Tavarez-Vega writing together during the 2023 conference.

Anthony was clearly agitated. For the first time since I had known him, I heard the 17-year-old’s soft-bass voice become rather sharp and loud as he and his best friend Timothy told story after story about their ongoing troubles. The troubles they told of were mostly with the school administrators, teachers, local authorities, and African American peers they had met since moving to the United States from Liberia a few years earlier. The following is a short excerpt from one of those troubling stories:

1 I don’t know how they- I don’t really understand

2 Because if you go tell the school they gonna be like, “Who’s doing it?”

3 Or they gonna be like [pause] “Well we don’t have no proof. We didn’t see nothing yet we don’t have no

4 evidence yet”

5 You tell (in there), they’ll say they don’t have no evidence

6 And then when you try to fight back, they say you fight and you getting suspended for fighting

7 But you try and defend yourself man, I, don- it just hard it just hard to- [pause] to get a way of

8 get along in this school or in the country in general cause whatever you do you still gets in trouble so

9 I-don- know

10 If you try to defend yourself, you get in trouble

11 You try to get away, you still in trouble so

12 Even if you go to the- even if you tell them – they won’t DO nothing about it, once nothing happen

13 they can’t do nothing about it

14 That’s the law: and [pause] I don’t understand the law.

In these few lines from Anthony’s emotional telling, we hear how confusing and tightly interwoven social structures like schools and the criminal justice system can be for some newcomers. Specifically, we hear about providing “evidence,” fighting back, defending oneself, getting along, and getting in trouble. So, what exactly is Anthony talking about—and who is causing all this trouble for him and his friends?

This essay examines the different kinds of trouble that many young people from Africa (like Anthony and Timothy) face when they migrate to the US. Based on this 2009 conversation between Anthony, Timothy, and me, and on more than 20 other conversations I had over the following years with fellow students at their huge suburban high school just outside of Philadelphia (“County High”), I understand these troubles to be multilayered. Nearly all of these young people from the vast continent talked about troubles with White American classmates, neighbors, teachers, and administrators who seemed to know very little about Africa and who believed various stereotypes about African people. They talked about the many times they were misidentified as “African American,” and they discussed the ways their Africanness, their Liberianness—or their specific ethnic identities—were often erased. Several young women told of the ways their bodies and bodily practices were treated as essentially different and sometimes as inferior. Meanwhile, many of the young men discussed troubles with the police and noted how trouble at school could easily lead to a court case (i.e., “catching a case”).

By making their conflicts “a Black thing,” and a peculiar one at that, teachers and others unintentionally invoked racist ideas about Black people as naturally and inevitably violent no matter where they come from.

Most African transnational students, students with personal and social connections to countries outside the US, also talked about troubles with other Black young people. In particular, they talked about troubles with their “Black American” peers, which included African Americans and Caribbean Americans. These troubles were well known in the Philadelphia area at the time because there were several highly publicized fights and physical attacks between African transnational and Black American youth in local schools. In fact, every few weeks, there would be a news story (on TV or in a local paper) about these fights or about general tensions between the communities. Unlike Anthony and the other African transnational and US-born students I talked to, their teachers, school administrators, and local news media often framed these fights and tensions as an intraracial issue, often by using or alluding to the phrase “Black-on-Black.” This essay digs into the tensions and examines the concept “Black-on-Black violence.” I will show how this indirectly shaped many young people’s experiences because of the ways it located the source of their problems within one or both of the groups involved. By making their conflicts “a Black thing,” and a peculiar one at that, teachers and others unintentionally invoked racist ideas about Black people as naturally and inevitably violent no matter where they come from.

Background

Inspired by the poignant and sometimes painful conversations I had with students at County High, I went on to spend the following 10 years researching the complex experiences of African transnational young people in the US and Liberia. Liberia is a small country on the coast of western Africa founded by African Americans in the 1820s, and it is the home country of Anthony, Timothy, and many other people with whom I worked. In other work, I write about relationships between Black people from different parts of the world in the midst of racism. Even though I have spent a great deal of time working with Liberian communities, because I am an African American woman, I try to be very careful about how I study and produce knowledge about African people, and in my work with young Liberians, I tend to critically examine the role of non-Liberians and the US in their experiences.

In that vein, this essay specifically focuses on discourse about the relationship between Africans and Black Americans by young African transnationals as well as by educators and the media—especially discourse about violence and conflict. That means I will look at the ways African students talked about their complicated relationships, and I will look at the ways teachers and the news talked about these relationships. I focus on discourse because it is more than just conversations or dialogue between people; it is also sets of beliefs, rules, norms, practices, and policies that shape how we understand the world, how we behave, and how we are treated by people and institutions. Because discourse is a product and producer of our social realities, it has the power to cause serious harm in ways that are hard to detect.

I focus on discourse because it is more than just conversations or dialogue between people; it is also sets of beliefs, rules, norms, practices, and policies that shape how we understand the world, how we behave, and how we are treated by people and institutions. Because discourse is a product and producer of our social realities, it has the power to cause serious harm in ways that are hard to detect.

Using ethnography to study the lives of young African transnationals in the Philadelphia area and young Liberians in Liberia’s capital city of Monrovia, I found that different stereotypes about Africans and African Americans (conveyed through discourse) not only impacted how members of these groups thought about and treated each other but also impacted how others (like teachers and journalists) characterized any conflict between them. I argue that these characterizations about their conflicts were often rooted in antiblack stereotypes and suggest that they contributed to the potential criminalization of both African transnational and African American youth.

The Trouble with “Black-on-Black Violence” Discourse

Based on numerous conversations and on my reviews of local media over the years, it seemed that among many educators at other local schools, community members and organizers, parents, and journalists, a generic “bullying” label was readily applied to physical conflicts, often with little or incorrect context or with no context at all. Some also referred to the African students involved as being from “war-torn” and “violent” countries. And, most either used or indirectly referred to the phrase “Black-on-Black violence.”

The discourse of Black-on-Black violence works to mark Black communities, distinguishing them from other communities by characterizing them as “naturally” violent. In general, people harm people they know or live among, and therefore violence is more common within racial and cultural communities than it is across them. Most White victims of violent crimes are hurt by other White people (Federal Bureau of Investigation 2015), most Asian people are harmed by other Asians, and so on. Notice, however, that there is no such thing as a “White-on-White” violence discourse or an “Asian-on-Asian” violence discourse. The “Black-on-Black” discourse therefore singles out the Black community and suggests that there is something peculiar about people of the same race being violent with one another despite the actual reality of how violence happens. While violent crimes are generally more common in poor neighborhoods regardless of racial make-up, the discourse of “Black-on-Black violence” has been used in US political discourse since the 1980s to suggest that violence in mostly Black neighborhoods is different from violence in other communities.

While violent crimes are generally more common in poor neighborhoods regardless of racial make-up, the discourse of “Black-on-Black violence” has been used in US political discourse since the 1980s to suggest that violence in mostly Black neighborhoods is different from violence in other communities.

Spread across the local, national, and international levels of discourse that swirled around and through County High, there was one popular Black-on-Black discourse about violent tensions between Black African-born students and African Americans that seemed to position the “American” students as the chief agitators and “African” students as victims. The few accounts that deviated from this were shared by African American students who saw the aggression as equally distributed and by teachers who suggested that there might be a special kind of African tendency toward violence by referring to conflict in Africa (specifically “child soldiers”) or to rumors about African youth gangs in the area. All things considered, nearly every mention of the tensions depicted young Black men (and some women as well) as uniquely and excessively violent and implied that the conflict between them did not seem to be based on anything other than the fact that they were all Black.

A few weeks after I interviewed Timothy, Anthony volunteered for the project again and this time requested to interview his favorite teacher. Mr. Perini appeared to be in his late 20s or early 30s and was White- and masculine-presenting. During a private conversation between us, he turned crimson when I asked if he had noticed any racial tensions at the school. After a long pause, he told me that the only issue he could think of was how a “bunch of the Black kids have problems with each other” and designated some as “African” and others as “American.” A deep shrug accompanied the following statement: “I just don’t know what the issue is.” Mr. Perini’s framing of the tensions reflected the vast majority of teacher commentaries: as examples of a “racial issue” and as a confounding and peculiar phenomenon. With the exception of two teachers, most introduced the topic of African-African American tension on their own when I asked about “racial issues” in the school or about their experiences teaching newcomer African students. The 8–10 teachers I spoke with about the tensions generally expressed not only a sense of uncertainty but also a kind of perplexity as to the cause of such tensions.

Another teacher, Mr. McKinney, used the specific phrasing “Black-on-Black” to name the racial tensions at the school that he found most concerning, but most teachers indirectly alluded to the concept by describing the tensions as a peculiar and concerning racial issue. They considered Black young people having problems with one another remarkable enough to deem it a “racial issue” yet made no attempts to explain what was racial about it or why they thought it was happening. For example, none spoke about certain individuals not getting along for personal reasons (like the situation in which one student had flirted with another’s girlfriend) and none mentioned how many of the new White, Asian, and Latine male students also got into frequent tussles with existing cliques. All that to say, the ways the teachers repeatedly connected certain conflicts under an umbrella of “Black students having problems with each other” suggested that they thought there were no logical explanations for these students fighting with one another other than that they were all Black.

…the ways the teachers repeatedly connected certain conflicts under an umbrella of “Black students having problems with each other” suggested that they thought there were no logical explanations for these students fighting with one another other than that they were all Black.

Student and Community Discourses: Avoiding Trouble and Critiquing the System

During my research, I listened to local stories and theories (from people from Africa, the Caribbean, and the Americas) about being Black in the US, and I paid particular attention to discourses about being Black in relation to White people and to other kinds of Black people. Although we all used different kinds of language, Timothy and Anthony, older African transnationals in the community, African American students and community members, and I pondered many of the discourses that helped shape how African transnationals and other Black people saw and treated one another.

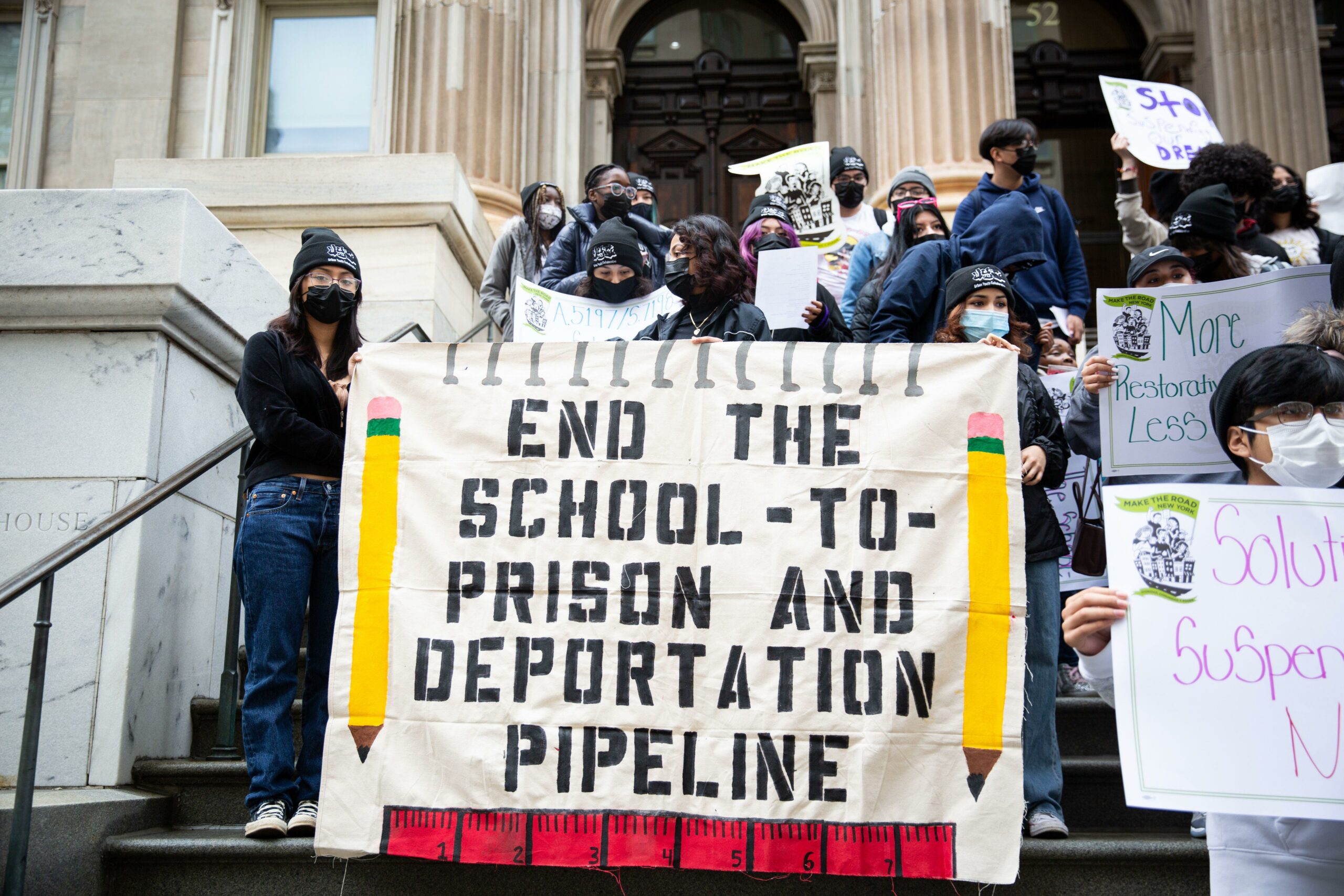

While there has been ample research conducted to show the connections between antiblack stereotypes in schools and the criminal justice system, I came to this conclusion largely because so many of these young transnationals’ narratives included astute statements that characterized what scholars call the “school-to-prison pipeline.” This concept refers to the ways students perceived as “troublemakers” are often treated as criminals via what many have described as the “school-to-prison-pipeline.” Anthony’s statement “That’s the law and I don’t understand the law” in line 14 is a great example of this because he referred to a school policy about fighting as “the law.” Upon learning more about the context of the school and community, I realized that he may have collapsed school authority and the criminal justice system into a single entity because the County High’s School Resource Officer and the local police sometimes arrested students engaged in physical altercations, which often led to them having formal criminal charges.

Like Timothy’s and Anthony’s stories, many of the narratives about trouble from the young men I spoke with would use several “legalese” terms, and most depicted themselves as honest and innocent in all of the conflicts. For example, they used terms like “evidence,” “victim,” “innocent” and “guilty.” These patterns suggest that they were very aware of the ways they and/or their peers were routinely criminalized by the government-school-criminal justice system. Therefore, telling their stories in this way helped present the tellers as good people, respectable social types, and/or blameless victims, rather than as “thugs,” criminals, bad kids, primitive natives, or other undesirable stereotypes of Black people that increase the likelihood of being disciplined, jailed, or murdered. In this way, such narratives may be read as discourses of protection or as defensive strategies against the threat of racist violence by school and local authorities.

Importantly, although many African-born young people complained about the tensions and conflicts they experienced with Black peers, they rarely attributed these troubles to their shared Blackness. They also almost never referred to the tensions as bullying but instead regarded them as different groups not getting along. Others referenced the conditions in which African Americans, or Black people in general, were living and had been living and cited these as factors in the tensions. One young woman explained that some African Americans felt like African immigrants did not appreciate all of the things for which African Americans have had to fight for in order to survive in this country. Specifically, she said something along the lines of, “They think we don’t know, but trust me, Liberians know,” differentiating Liberians from other African immigrants due to Liberia’s unique connections to Black America. Another young man from Ghana who attended the local community college and owned a small business in West Philadelphia shared that he thought African Americans felt that African immigrants were taking already scarce resources from them regarding city services, business loans, community grants, education fellowships, and jobs.

Altogether, while some students’, community members’, and educators’ theories about the tensions and conflicts between African-born and US-born Black young people directly or indirectly upheld a notion of African American pathology, a number of the students and community members attributed this pathology to antiblack racism and ultimately depicted it as the source of many troubles. That is to say, they may have felt that African American people or culture were troubled, and that African American youth were doing troubling things, but most diagnosed racism to be the cause of the trouble.

So, how do all these discourses about the tensions between the groups relate to authority and Anthony’s earlier comments about trying to get along in this country? In general, the young men from Africa with whom I spoke and spent time talked about these conflicts in ways that almost always related to some kind of authority or power structure. Whenever I asked about their relationships with African Americans they frequently referred to “the country,” “the school,” and “the police” as entities for which it was important to show that you are not a “bad kid” or a “bad” kind of Black person. Many of them did this by sometimes talking about the other group in negative ways and juxtaposing themselves to those bad or problematic people. However, most of these kids would also blame these same authoritative entities—and the ways they were “unfair”—as the reason for the other group’s shortcomings and as the reason they were causing trouble.

Conclusion

Over time, this plethora of individual stories, commentaries, and conversations with several African transnational and African American young people revealed the Black-on-Black rationale for the tensions between them to be quite reductionist and not well founded. Instead of accepting that these troubles were due to Black people being inherently anti-social, uncivilized, and violent—as the Black-on-Black discourse implies—I learned that there were a number of complex factors in these tensions. They ranged from two people just not liking each other, to cliques clashing, to xenophobia about any kind of newcomers, to internalized antiblack racism. Collectively, their discourses almost always referred to the structural (economic, political, historical) factors in and motivations behind interethnic Black relations in and outside of school. Their stories and lives illuminate the extensive labor of trying to safely and beneficially situate oneself within a vast field of antiblack stereotypes and systemic racism. All told, discourses that directly or indirectly suggested that Black people are more or uniquely predisposed to violence influenced the ways these young people presented themselves and talked about others—and, possibly, how they treated one another.