When I started using they/them pronouns, I noticed that certain people struggled to get my pronouns right, including my linguistics professors. They kept calling me “he” or “she” instead of “they.” This confused me—shouldn’t linguistics professors be even better than everyday English speakers at getting pronouns right?

What was even more mysterious was that these professors didn’t notice their own mistakes—and they used “they” to refer to a single person just fine at other times, like saying “someone forgot their backpack” or “a student turned in their homework.” It wasn’t clear to me why they didn’t notice using the wrong pronouns for me, and I also couldn’t understand why they could use “they” for a single person sometimes—just not when talking about me.

So, I did what any good linguist would do: I started researching this odd quirk of language. It was clear that something unconscious was going on, because even people with advanced degrees in the science of language didn’t notice their own word use. My core research question was this: what’s going on with pronouns like “they,” and why is there a disconnect between some uses of “they” and others?

One of the first things I had to do was explain the difference between those different uses of “they.” But I wanted to focus on just singular “they,” meaning “they” referring to just one person. Here are some examples of what I mean:

(1) Someone always forgets their backpack.

In example (1), “someone” is technically singular because it might refer to a single person, but the speaker doesn’t know who it is. So, it’s also talking about a bunch of different possible people. That’s what linguists call the indefinite singular “they”: it’s not clear who “they” is referring to in sentence (1).

Another different type of singular “they” also exists:

(2) The ideal student never forgets their backpack.

In example (2), “the ideal student” is singular, but it’s not referring to a real, specific person. It’s just referring to the idea of a person. Linguists call this kind of singular “they” the generic singular “they,” because it’s a generic idea of a person, not a specific person. But it’s still singular.

And then, finally, the last type of singular “they” I wanted to learn about was this:

(3) Kirby always forgets their backpack.

In example (3), “they” is referring to a single specific person (me)! This was the one my professors kept messing up, even though they said things like (1) and (2) all the time. So, it was clear that sentence context mattered: if you’re talking about a specific person, then that might be different from a generic or indefinite person. In (3), you know exactly who you’re talking about.

What I needed to do was design a linguistics study to figure out if my instinct was right that people were treating these different kinds of singular “they” differently—and if they were, why? Was it something about the linguistics of pronouns or something about the context of the sentences… or both?

So, how do you find out what’s going on?

In linguistics research, there are a number of ways to figure out what’s going on in someone’s unconscious language use. One is to try to see what they say in a natural conversation, which tells us how people are using language in everyday life. The other way is to see how people react to different examples, which tells us a little bit about the unconscious patterns in peoples’ minds, even when it’s something that doesn’t necessarily come up in their everyday lives.

To figure out what was going on with singular “they,” I decided to tackle it from both directions. Over the course of 2018 and 2019, I did two studies: one where I interviewed people and analyzed what they said in conversations and another where I asked people to read sentences and give their gut reactions.

In the first study, I wanted to see whether people were using these different kinds of singular “they” in normal conversations. The trick is, in order to check that, I had to make it so that their conversations included lots of pronouns—including “they,” but also “he” and “she”—so I could compare them. And getting someone to use “they,”“he,”and “she” means I needed them to be talking about someone. What I did was I interviewed people in pairs: first two people (and me) would all have a conversation together, and then I would talk to each of them separately. The idea was to get recordings of people talking about someone else, so I could compare the pronouns they used, and I would know whom they were talking about.

I also noticed a pattern: my younger participants, who were in their twenties and early thirties, used they/them pronouns a lot more, and my older participants (over 50) barely used it at all. The people in the middle (late thirties to forties) used it a medium amount.

What I found was interesting: people used singular they/them pronouns much more than I expected. Part of that was probably because I intentionally asked nonbinary and trans people to be part of the study. But I was surprised at just how much people used they/them/their pronouns to talk about a specific person (usually their interview partner). I also noticed a pattern: my younger participants, who were in their twenties and early thirties, used they/them pronouns a lot more, and my older participants (over 50) barely used it at all. The people in the middle (late thirties to forties) used it a medium amount.

This was super interesting to me, because I hadn’t considered that the thing going on with my linguistics professors might just be because professors tend to be a little bit older. But I wasn’t sure: was this just a coincidence because of the people I happened to interview, or was this a larger trend in society? To find out, I designed a second experiment, one that could reach a much larger number of people—and not just people I could take the bus to in Seattle.

My second experiment was a survey of over 700 people, conducted online. The good thing about online surveys is that anyone with an internet connection can take part, and it takes a lot less time for them to do it. For the online survey, I crafted a bunch of sentences, with the plan of asking people about their gut reactions: “Does this sound natural to you?”

The sentences I asked people to react to were testing two different aspects of pronouns: so I had sentences with “he,” “she,” and “they” (all singular!), and I included sentences that were indefinite(not sure who it’s about, might be one or more people), generic (about a hypothetical person, who may or may not exist), and specific (using a name—I included masculine, feminine, and neutral names). In the examples below, I show how these combinations look all together:

I also asked people to share a bit of information about themselves: their age, gender, where they were from, their ethnicity, and whether they were trans or nonbinary themselves.

What did I find out?

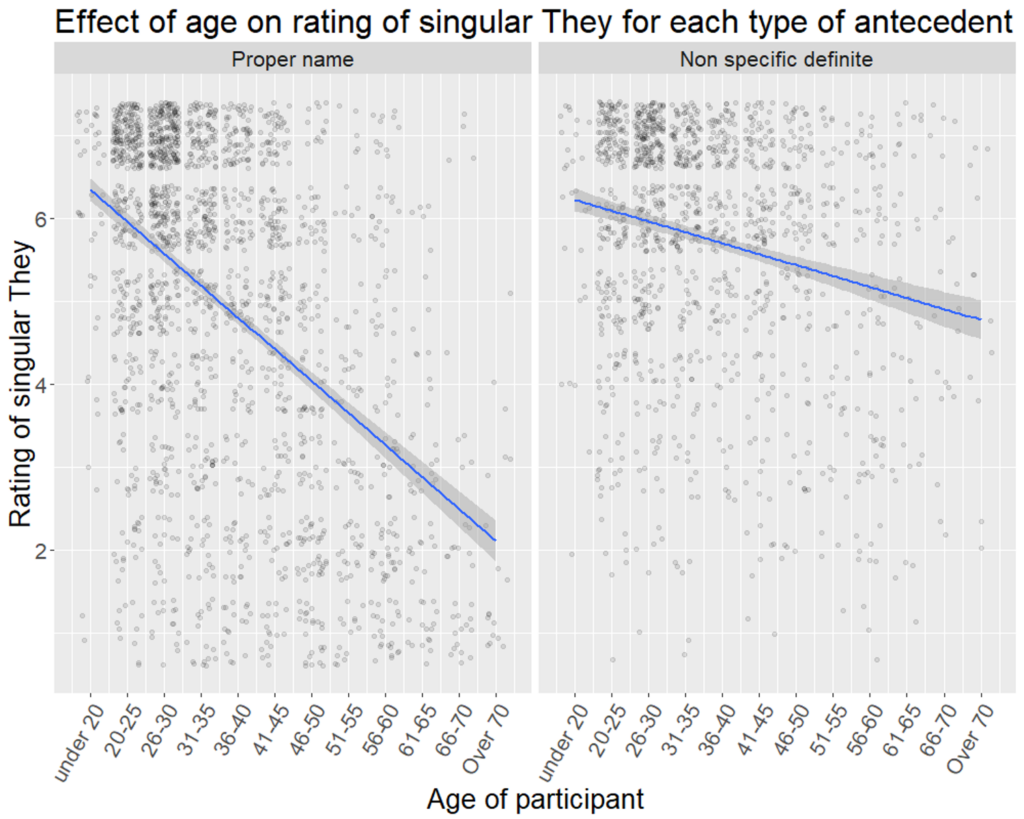

What I found out was that peoples’ identities—especially their age and gender and trans identity—did affect whether they thought sentences sounded natural, but only for sentences where “they” referred to a specific single person (like in (3) above). That was exactly the type of “they” that made people misgender me (by calling me “he” or “she” instead of “they”), so this was really exciting to see. In Figure 1 below, I’ve separated the ratings out into two groups: on the right, I’ve grouped together generic and indefinite sentences, and on the left, I have only the specific sentences. The x-axis shows the age of each person who took the survey. The fact that the line slopes down means that older people rated those sentences lower, and younger people rated those sentences as higher (meaning they sounded normal and natural).

The fact that age was an important factor shows something really important about the English language: it shows that the language is changing.

When languages change—like when Latin changed to become Italian and Spanish, or when Old English changed to become Middle English and then finally the English we speak today—it doesn’t happen all at once. Language change is a slow process, made up of lots of little changes. In the history of English, for example, people slowly stopped using “thou” and started using “you” in more contexts. It wasn’t like everyone woke up one day in the 1800s and said, “‘Thou’ is totally out, we’re all going with ‘you’ now!” Instead, younger people started using “you” more and more, and “thou” less and less. Each generation pushed that language change a little bit, until it finally was (mostly!) all “you” and no “thou.”

The fact that age was an important factor shows something really important about the English language: it shows that the language is changing.

What that means is that, if you took a snapshot right in the middle of that change, you would get a picture where younger people were doing something different than older people. Age can be a kind of window into language change that’s going on, even though it’s hard to measure the language over a long period of time.

And what’s going on with “they” seems to be very similar—but again, only for “they” referring to a specific single person. The fact that older people found it less natural means it wasn’t really a part of their unconscious language, but it was becoming more and more a part of the language for younger speakers.

The other really interesting thing about the survey is that I gave people a chance to write their thoughts and comments, and a lot of people used that space to directly say that they knew language was changing. When language changes in subtle ways, speakers sometimes don’t notice, but for this one, people are aware of it, even though they’re not exactly doing it on purpose. Older people commented on the survey that they were aware that “they” was being used as a gender-neutral pronoun more and more, but they said that they still struggled to keep up with the language change. This is also common: because language is such an unconscious part of our lives, we don’t always have the ability to perfectly control what words we use, even if we want to.

What does it all mean?

The results of my survey made me feel less hurt by my professors who were trying their best, but still messing up: they were older, and this part of language was mostly an automatic habit. They weren’t misgendering me because they didn’t really see me as nonbinary, but mostly because there was an older form of English in the unconscious language part of their brains.

Knowing that language change is a natural part of the world means we can change our perspectives on it.

This also made me wonder whether other languages were undergoing similar language changes around nonbinary language. As it turns out, they are! I’ve only talked about English so far, but the Gender In Language Project has information about Spanish, Irish, Danish, Tagalog, and more! Pronouns are just one small part of the way that languages talk about gender, and pronouns aren’t necessarily just all about gender. Languages can mark gender on nouns, adjectives, and even verbs! English is in the minority when you look at all the languages of the world, too, because most languages don’t mark gender on pronouns.

What should we do about it?

Learning all this information about pronouns matters to me, not just because misgendering hurts my own feelings, but also because studies show that it can have a really big impact on peoples’ happiness, self-esteem, and sense of safety. And knowing that the English language is changing right now means we can try to increase peoples’ linguistic awareness. If you think carefully about the pronouns you use, then you’re more likely to use the ones you want to use, which will hopefully mean that we accidentally misgender people less and less. Knowing that there’s a difference between different types of “they”—specific, generic, or indefinite—means that people can think critically about when they use “they.” And knowing that language change is a natural part of the world means we can change our perspectives on it. It’s not that “kids these days are ruining English.” Instead, English is a living language that is always going to change and evolve, just as societies and cultures change over time, and we can watch and appreciate it as scientists.