Ever wonder why ads that are supposed to be diverse and inclusive are often called out as racist? I did, and I was especially curious about who makes the ads and what the actors in them think about the negative stereotypes they portray. Racist ads today may seem like the exception rather than the norm but are far more common than expected during our diversity-focused times. They actually continue a longstanding tradition in American advertising to uphold White supremacy.

This article offers a look at racial and linguistic diversity in US advertising as well as how this industry handles consumer accusations of racism. Messages in advertising affect everyone because they are ubiquitous, appearing on every screen and platform we encounter in everyday life. Advertising has always been a tool of White supremacy, with ads made for White audiences. Even when they may not seem offensive, they often reinforce White supremacy. For example, advertisements for skincare brands have, for well over a century, juxtaposed White and BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, and people of color) people by upholding Whiteness as ideal and anything else as less, despite repeated academic and audience critiques. Even when consumers voice complaints about ads being racist, corporations are reluctant to take responsibility and suggest the audience misunderstood their intention.

A linguistic anthropological approach to understanding meaning in advertising offers a way to analyze and talk about ads. I apply two concepts from linguistic anthropology to analyze two case studies of skin care brands. The first case study featuring skincare brand Nivea pairs images of Whiteness and Blackness with terms widely utilized in Europeans’ conquest of non-White populations across the globe. I discuss how words, when paired with images, invoke not just descriptions of the product but also social meanings. The linguistic anthropological concept of “indexicality” shows how certain words can index, or indirectly reference, racist ideas. The second case study uses skincare brand Dove to demonstrate how corporations respond to consumer accusations of racism. Corporations often sidestep performing a real apology when consumers take to social media to call out ads as racist. Instead, they offer “sorry, not sorry” statements that are far more damaging than what Demi Lovato declared in her 2017 song of that same title.

Despite efforts to diversify this industry, advertising and corporate culture remains steeped in Whiteness. In this environment, White standards of language and aesthetics are simply regarded as “normal.”

Between 2009 and 2012, I conducted ethnographic field research in ad agencies to understand why racist ads keep getting made, how ad executives respond when audiences accuse them of being racist, and why this pattern repeats. I observed and interviewed executives in advertising agencies in New York, Los Angeles, and San Francisco, focusing on their efforts to reach minoritized consumers. I found that most people who make ads (ad executives) and the brands that hire them (advertisers) tend to be thoughtful, progressive, liberal people. Yet despite efforts to diversify this industry, advertising and corporate culture remains steeped in Whiteness. In this environment, White standards of language and aesthetics are simply regarded as “normal.” For instance, advertisers prefer to cast American-accented English and white talent as the leads. When clients requested ad executives feature greater diversity, some preferred ethnically ambiguous talent who were difficult to identify as being from a specific place or cultural group. Without any distinctive clothing or language that signaled their ethnic or linguistic background, diversity becomes synonymous with anyone who does not look white. While some ad executives and corporate brands agree that this is an ideal way to represent diversity, it can backfire for BIPOC consumers who struggle to identify with ambiguous brownness. When this White ideal is imposed upon BIPOC populations, it reinforces the silent power of White supremacy.

White supremacy is a system of thought that developed in Europe during the enlightenment era. It was built by and intended to serve White people to protect their property, wealth, and social standing. Its ideology deems White people superior to non-White people in every way. Accordingly, White lives are worth more than BIPOC ones, with every echelon of society designed to ensure White social, economic, and political advancement. Centuries ago, when White Europeans first settled in an already populated North America, they did not treat Native Americans as equals. Written accounts of this time period describe Native people as uncivilized and their languages as primitive and animal-like. Black Africans sold as slaves or indentured labor were treated like property rather than human beings. These characterizations justified ongoing violence and prejudice against these groups, as well as against non-White settlers from Asia and indigenous Central Americans. Late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century ads reflected these social beliefs and often included caricatured BIPOC characters as foils to Whites, to underscore the aspirational value of whiteness. Even though the recent emphasis on diversity has prompted more careful executions of racial difference, ads still consistently reproduce racial stereotypes.

Most ads are intended to grab your attention visually, but language can also play a major part in communicating brand identities. Since the mid-nineteenth century, print ads and marketing materials like flyers, trade cards, and billboards have used animal-like visual representations of BIPOC populations, each with their own “registers,” or specialized language varieties, to entertain White audiences. Remnants of these early representations persist today in advertisements and comprise the foundation for modern racist slurs. Linguistic anthropologists have studied how “Mock Spanish” (“that’s no bueno”) ridicules Spanish speakers and perpetuates stereotypes about immigrants from Central and South America, as well as how “Yellow English” (“ching chong,” “flied lice”) is a nonsense register consisting of how White people believe Chinese speakers sound. Black English, an actual language, is appropriated for attempted humor (“We be down, homey!”), while the overly-simplistic, often monosyllabic “Injun-speak” depicts Native Americans as lacking capacity for complex thought.

Ads today rarely contain such overtly racist language, but they use images and words that further the ideal of Whiteness. Nivea brand skin care products, which are all a distinctive white color, have carelessly used “white” as an adjective and noun, paired with beauty images of White people and other provocative text. Their 2017 campaign “White Is Purity” included print ads pairing the phrase with a picture of a White woman with long silky blond hair in a plush white bathrobe. Although intended for audiences in the Middle East, the main text is English and subtitled below in Arabic, allowing any speaker of either language to understand it. While the ad was already problematic for idealizing Whiteness in a region of the world where lighter skin tones are the ideal, since Western Asia is rife with colorism, the ad drew further outcry as it circulated globally on the internet. The term “purity” has long been linked to being White without any “mixing” of blood from non-Whites. Blood quantum, or the percentage of each racial or ethnic group that can be identified in a person’s heritage, once relied only upon visibility and socially passing as White.

Consumer challenges to the corporations underwriting these images have become far more rapid and effective with the widespread use of social media. Instagram, Facebook, and X (formerly known as Twitter), as well as groups on WhatsApp and other messaging apps have emerged as effective sites to counter ingrained racism. They allow consumers to amplify their voices through hashtags and circulate comedic critiques through memes, such as the numerous entertaining memes of the Nivea ad with ironic or critical text replacing “White is Purity.” In a less amusing reaction, an actual White supremacist group posted on Nivea’s Facebook page: “We enthusiastically support this new direction your company is taking. I’m glad we can all agree that #WhiteIsPurity.

This was not the first time Nivea had leveraged the look of its product to match a racial ideal. A 2011 Nivea print-ad campaign called “Re-Civilize Yourself” featured a Black man holding a version of his own face with an afro and facial hair. In this bizarre image, the man’s “before” face dangles like a Halloween mask in his hand, its negative value unequivocal. The word “civilize” has been used for centuries in efforts to transform colonized and enslaved people into those who could meet Euro American cultural and linguistic standards. Here, it promotes the very same values, that Black people are not fit for Western society without sufficient self-transformation. Nivea offered them a means to become civilized by shedding their dark, hairy selves in favor of a lighter, whiter-looking version ready for the corporate world.

Other ads that are called out for being racist may not initially appear so. Dove skincare released a video on its Facebook page in 2017. It shows women of different races transforming from black to white as they take off skin-colored t-shirts. A Black woman removes her shirt to become a White woman, who removes her shirt to become a Brown woman, whose undressing returns us to the first of the three models. Outrage was soon followed by calls to #BoycottDove on Twitter. Critics who labeled it as racist raised questions about skin color and representation, while supporters of the ad saw it as a commitment to diversity. Dove took down the ad and offered several statements in response, expressing that it had “missed the mark” and that their ad was “tone deaf.” They additionally promised that this feedback “will help in the future.”

But did they actually apologize, and for what? The speech act of saying “we’re sorry” performs an important action, one that differs from referential or descriptive talk, such as “Dove soap is white.” Linguistic anthropologists consider apologies to be part of a special class of words called “performatives,” because saying certain words can bring about social actions in the world. “Performativity” is a philosophical concept that identifies a category of words called “performatives” and the sequence of events required for these action-performing terms to be socially understood and accepted. For instance, saying, “I bet you $5” is not the same as saying, “American money is green,” since the former actually links the material world with the linguistic. “I promise,” “I swear,” and “I do” (at a wedding altar) are all performatives because the words perform those actions. When brand CEOs say, “We’re sorry” and say they will not repeat a mistake, consumers understand this as an apology for the wrong committed as well as a promise to not recreate it. Yet, corporate apologies can just as easily sound like “sorry, not sorry” performatives, through such phrases as, “We’re sorry people were offended,” therefore putting the blame of offense on the viewer rather than the maker of the ad. In this way, linguistic anthropologists can use performatives to illustrate the difference between sincere apologies and statements that place the blame on offended viewers of an ad for misunderstanding its true intent.

Advertising featuring BIPOC talent seems like an ideal way to promote diversity, equity, and inclusion, but so often, it achieves the opposite result.

Like many corporate apologies, Dove’s missive on Facebook attempted to explain the brand’s intent, rather than what actually caused offense: “An image we recently posted on Facebook missed the mark in representing women of color thoughtfully. We deeply regret the offense it caused.” In another apology, Dove reiterated that it is “committed to representing the beauty of diversity.” Dove apologized about how the ad made people feel, not the racist nature of the ad itself. In all of these statements, Dove apologized for the affront the ad caused, and even admitted that they were mistaken in their approach, but still adhered to the “celebration of diversity” they wanted to depict. By justifying their choices rather than apologizing for them, they reflect the blame back at the offended audience members for not supporting diversity efforts.

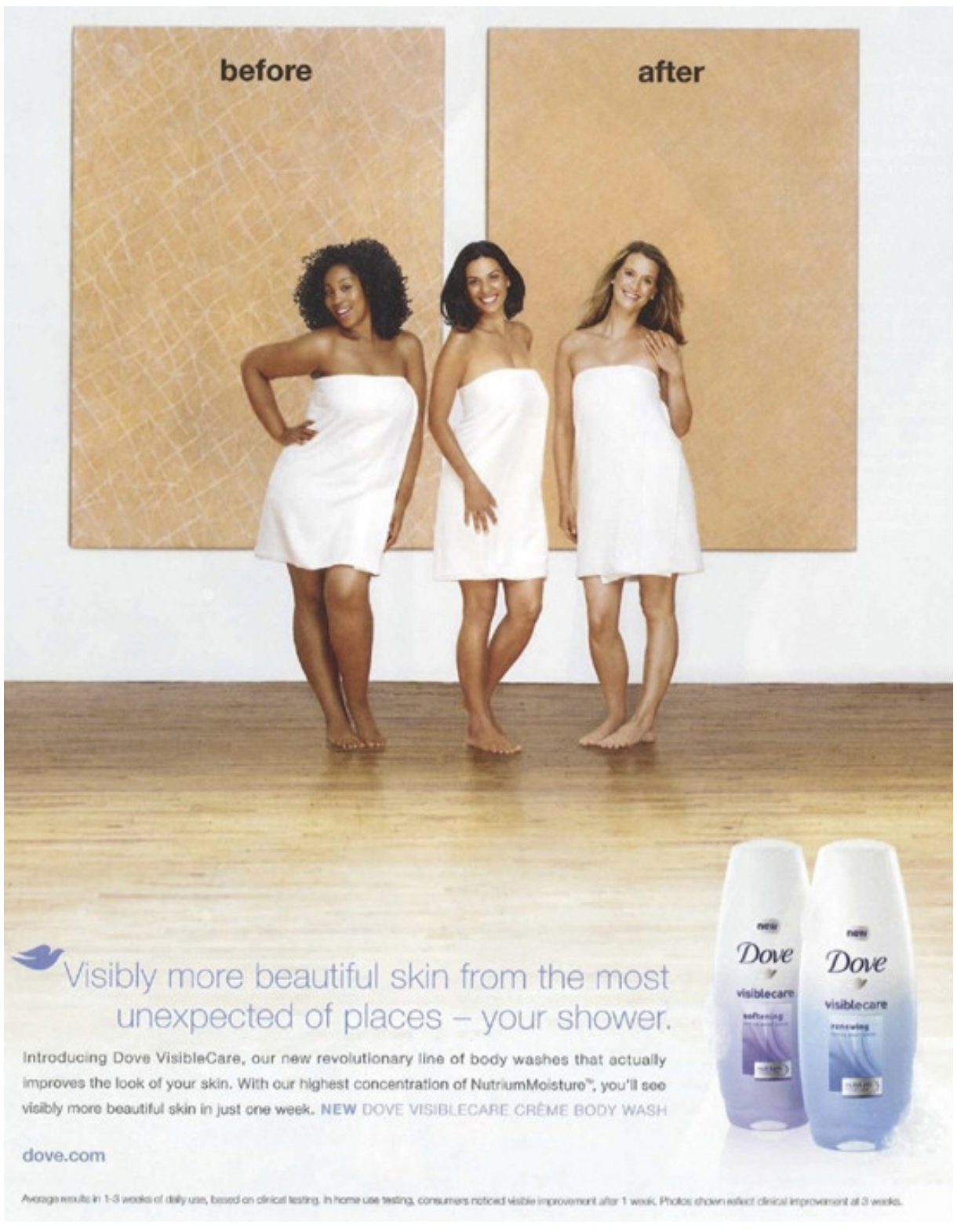

Critics on social media were quick to point out that this was not the first time that Dove had come under fire for depicting diversity in its ads. In 2011, the brand ran a campaign promoting body wash that showed three women of different skin colors standing in a row. Copy reading “before” appeared over the woman with darker skin color, while the word “after” appeared over the lighter-skinned woman. Dove responded by claiming that all three women were meant to represent the “after.” Some critics tweeted images of the 2011 and 2017 ads next to each other, underscoring that Dove had learned little since this debacle. Actors in the ads usually do not speak out about such controversies, but the 2017 ad’s Black model, Lola Ogunyemi, expressed criticism in The Guardian that Dove simply pulled the ad rather than stand by their casting of a darker-skinned Black model. In other words, the selection of darker-skinned talent was an actual win toward racial equality because it challenges colorism, which privileges light over dark skin. Casting Ogunyemi was a bold choice in an industry that still values ethnic ambiguity, but in this particular ad, it unfortunately furthered, rather than challenged, dominant norms of whiteness.

At a time when society is focused on diversity and inclusion, ads still uphold Whiteness as the ultimate aspirational goal. Advertising featuring BIPOC talent seems like an ideal way to promote diversity, equity, and inclusion, but so often, it achieves the opposite result. Advertising executives who make the ads do not intentionally use racist language varieties or images. Even without these, racist messages can be communicated in more subtle ways. Likewise, the corporations that hire advertising executives to represent their brands are ready to perform remorse when their vision of diversity does not align with audiences. Brands who repeatedly perform “sorry, not sorry” apologies show how even if corporations promise to avoid racism moving forward, they are most likely just repackaging it in subtle ways. For all these reasons, it is vital to keep thinking critically about advertising and about the work language does.