Let’s start with a memory. Try to recall a moment when you chose to remain silent, even when you knew you had a lot to say. Why did you stay quiet: was it an expression of fear, of anxiety, of some other feeling? What’s it like to be silent at school, a place where you’re supposed to participate in classroom conversations to show that you’re a “good” student?

Meeting Aurora

Aurora is an undocumented student from Mexico. An undocumented student is a citizen of the country where they were born who immigrated to the United States without obtaining the U.S. government’s permission to live in the country. She knows what it’s like to be an excellent student and she also knows what it feels like to be silent at school. I’ve known Aurora for over ten years. I met her in 2013 when she was a fifth grader at P.S. 432, a public elementary school in Brooklyn, New York. Now, in 2024, she is in her junior year of college as an honors student at the City University of New York (CUNY).

In this article, we’re traveling back in time with Aurora to 2013. Back then, she was just ten years old.

In the following pages, we’ll think about what it means to grow up undocumented in the United States (U.S.) by listening to what Aurora said (and what she didn’t say) in her fifth-grade class.

Meeting Aurora’s family

Aurora has grown up in a “mixed-status immigrant family.” Although there are many different ways to refer to “undocumented immigrants” (the Migration Policy Institute, for example, uses the term “unauthorized”), I follow the example set by organizations like the New York State Youth Leadership Council (NYSYLC, YLC for short)—the first undocumented youth–led nonprofit in New York—who refuse the language of illegality and proclaim that they are “undocumented, unapologetic, and unafraid.” This means that some family members have papers (documentation issued by the U.S. government to someone they have authorized to visit or live in the U.S.) and some don’t (because the government did not grant them permission to enter the U.S.). Some of Aurora’s loved ones—like her parents, for example—are undocumented immigrants who live with the fear of being detained or deported by the police. Aurora herself is undocumented but her younger sister is a U.S. citizen.

When the topic of immigration would come up in elementary school, Aurora would face a dilemma: should she talk about immigration or not? She would choose silence over speech because it was the best way she knew to keep herself and her family safe.

People who live in mixed-status families and have different kinds of papers also have very different access to things that all people should have: health care, affordable higher education, the freedom to travel to see their loved ones, and more. Living with these stark inequalities shapes the experiences of everyone in a mixed-status family. Children grow up aware of these differences from a very young age. Mixed-status families like Aurora’s believe that education is so important because it can help them access more opportunities—it’s a big part of why they came to the United States!

Parents and children also feel a big responsibility to protect themselves from people and policies that want to remove them from this country. So when the topic of immigration would come up in elementary school, Aurora would face a dilemma: should she talk about immigration or not? She would choose silence over speech because it was the best way she knew to keep herself and her family safe. This was challenging because she always tried hard to be an excellent student by speaking up and participating in class. By listening to Aurora’s words—and also to her silences—we can better understand how it is that schools (and our public systems more generally) can produce fear and anxiety for children and young people growing up in mixed-status families.

Let’s visit Aurora’s fifth-grade elementary school classroom to see what I mean.

Going back in time to P.S. 432

When you walk up to Aurora’s elementary school, the first thing you notice are the murals alongside the building. They were painted by a community organization and by some of the kids, and they represent different themes related to immigration. Aurora was part of the mural painting and even signed her name on the wall along with the other artists.

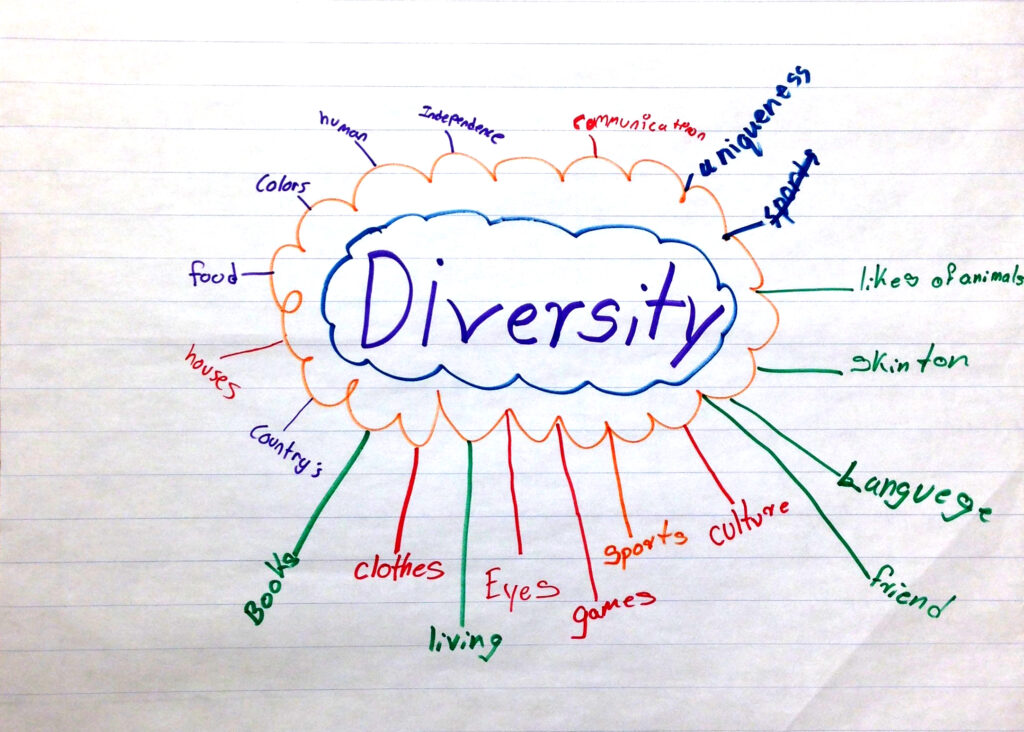

Imagine going into the school building on a hot day in May 2013, walking down the hallways, and entering a room where children were working in small groups. You join a small group of 3 students—Aurora, Nellie, and Sara—plus 1 teacher, all working together to define the word “diversity.” The children create a word web on a large sheet of chart paper. They write the word “diversity” in the center of the page and draw a big circle around it. As they brainstorm other words associated with “diversity,” they add lines branching out from the circle. This is what this group’s poster looks like in the end:

Listening to Aurora

How did the group end up with these words? Aurora had volunteered to write her group’s ideas on the poster, so she held the markers in her hand for most of the activity. Let’s listen in as she and her classmates—Sara and Nellie—talked about what diversity meant to them. I’ve numbered each of the lines so that you can follow along more easily.

1 Nellie: Countries, COUNTRIES. Don’t write IMMIGRANT! Write COUNTRIES!

2 Aurora: CULTURES instead

3 Teacher: Cultures, cultures, cultures

4 Aurora: Cullllltuuuures

5 Nellie Uniqueness

6 Aurora: Countries. I have another one. Um. Likes?

7 Nellie: Colors colors.

8 Aurora: I already put SKIN TONE.

[…]

9 Nellie: Border. Cause some people cross the border. And some people DIDN’T.

10 Sara: Independence.

11 Nellie: Yah, independence.

12 Aurora: Chill, I won’t put that. I’m not putting that. I’m not writing nothing. I don’t wanna write anything.

13 Nellie: Independence

14 Aurora: GAMES!

15 Sara: Language. Immigration.

16 Nellie: Oh yah uh write language. Somebody write language.

17 Aurora: I’ll write language

Aurora cared a lot about what her group was saying and, since she had the markers, she was really vocal about which words she would and would not write on the poster. One of Aurora’s reactions was to change the subject when immigration-related topics came up. One student started off with the word “countries” (line 1) and Aurora reframed with “cultures” instead. Even though she finally wrote down “countries” (in line 6), she kept trying to switch to neutral topics such as “likes” and “games”.

Aurora made a clear decision to remain silent when her classmate Nellie said “border,” explaining that some people “cross the border” while others “didn’t” (line 9). Aurora put an end to that conversation by decisively saying she would not write down the word “border” (line 12). Nellie dropped the subject, and Aurora tried to change the topic to “games” instead (line 14). The activity ended when Sara said “language” and “immigration” (line 15). Aurora ignored the word “immigration” while instead repeating and writing “language” (line 17). Throughout the activity, Aurora participated, but she also worked hard to steer the conversation away from topics like immigration and borders.

Children growing up in mixed-status families not only grow up aware of their families’ incredible strengths; they also grow up learning about the risks their families face living in the U.S.

What do you make of Aurora’s speech and of her silences? What does she mean when she says, “Chill, I won’t put that,” and refuses to write the word “border?”

What can we learn from Aurora?

After spending ten years getting to know Aurora (and other children like her growing up in mixed-status families), I have observed that young children learn what to say and what not to say in order to protect their families. In the field of education, adults—like teachers, principals, journalists, professors—might assume that children are unfamiliar with “grown-up” topics like citizenship, deportation, and nationality. They might assume that undocumented children like Aurora don’t realize what it means to not have papers until they are teenagers applying for a driver’s license or financial aid for college.

In schools, educators are asked to teach about immigration as a subject (in social studies, for example) but they are never allowed to ask students directly about their immigration status. This policy is important because it can protect the rights of undocumented students by making sure that they are not singled out, excluded, or mistreated because of their immigration status. But this policy can also lead teachers to think that immigration status doesn’t matter to students and their families. Teachers might think that immigration is irrelevant to schooling, but we have already seen that it matters a lot to students like Aurora.

By listening to Aurora’s words—and also to her silences—we can better understand how it is that schools (and our public systems more generally) can produce fear and anxiety for children and young people growing up in mixed-status families.

As someone who spends time hanging out with kids at home and school (I’m the kind of researcher known as an “ethnographer”), I know that children do, in fact, know a lot more about immigration than adults think they do. Children growing up in mixed-status families not only grow up aware of their families’ incredible strengths; they also grow up learning about the risks their families face living in the U.S. Kids know who in their family has papers and can travel back to their country of origin, they know who can go to one kind of doctor or another because they have or don’t have papers, and they worry about their parents, aunts, or siblings being detained or deported. As a result, they learn what topics to avoid talking about in public so that they can keep their loved ones safe. This is what we saw Aurora doing in school in the example above—she was making on-the-spot decisions about what she could say about immigration based upon the risks of being deported that her family faced.

This sense of responsibility is really strong for children who grow up in a time when the U.S. government considers immigrants to be a threat and a problem. Children growing up in the U.S. after September 11, 2001, are especially aware of this perception. Since that time, the government has moved from patrolling not only the country’s borders but also its streets and neighborhoods. Children like Aurora began to understand the risks their families faced at a young age. When Donald Trump was elected president, they felt the hate that U.S. politicians and their supporters could express towards immigrants, and they felt fearful as a result. These children—students and friends in our classrooms—learn an early set of lessons about how to protect their families, loved ones, and themselves from the risks of disclosing their immigration status even as they also learn to be proud of who they are and where they come from.

Why does this matter?

Why does it matter for you and your teachers, and for Aurora’s teachers, to listen to her experiences? Aurora’s story matters because she is not alone in her experiences growing up in a mixed-status family. According to 2021 estimates, more than 16.7 million people live in mixed-status households that include at least one undocumented member. Approximately 6 million of the people in these households are younger than 18 years of age. Estimates show that over half a million of them attend K-12 public schools. A little less than half a million undocumented students attend college.

One reason for all of us to know more about undocumented students’ experiences is so that we can help to make our schools more welcoming places for all students. When we become curious about each other (Why is my friend quiet today? What it is like for them to see police officers in our school? How might a classmate feel when another student or teacher raises the subject of borders and citizenship?), we may begin to notice how school policies and our actions impact others. This can help us to be kinder and more understanding of one another. If we start here, we can then build towards working together to fight for fairness and access for all of us.

Another reason to care about students from mixed-status families is to help ensure that they get the information they need to be successful in school without having to put their families at risk. No student should ever have to say, “My mom is scared to sign me up for school lunch because she doesn’t have papers” or “I can’t apply for financial aid because I don’t have papers.” Teachers should assume that they have mixed-status families at their schools and—without asking about anyone’s immigration status—they should seek out information about opportunities that all of their students can be eligible for.

A third reason to learn about the experiences of immigrant and undocumented students is so that we can join with other people and organizations working to change unfair policies that impact people living in the U.S. without papers. As friends and peers, neighbors and educators, we can help to share information about these important efforts. Check out the work of the New York State Youth Leadership Council, the first undocumented, youth-led organization in New York City. And see the great things happening at the CUNY Initiative on Immigration and Education to support educators in becoming advocates for their immigrant students. Please read my book, Knowing Silence: How Children Talk About Immigration Status at School, to read more about Aurora and her friends.

In recent years, those communities most directly affected by our current national policies have also been the most fearless leaders in calling for change. By learning from undocumented students and children from mixed-status families, by listening to them and witnessing their everyday experiences, we can break through polarizing debates about immigration and advocate together for more inclusion. When any one of us is treated more justly, the world becomes a better place for all of us.