Language education is often not just about language; rather, it is one of the ways teachers learn to see, hear, and treat students as successes or failures in relation to the goals of schooling. Consider the following story, which comes from my time teaching at an after-school program called Urban Pathways in Southeast, Washington, D.C. I often used to take a few of the children down to the local Giant Grocery Store to choose snacks to eat during and after the homework hour. On one trip, on a hot afternoon just before the 2011 school year ended, fourth grader Alisha noticed a value deal for a bigger packet of Hostess snacks and told the group that we should buy the bigger size rather than two of the smaller ones, proudly noting that we would save a small sum of our snack budget. But her older brother Joseph, a fifth grader who struggled with math, disagreed: he had looked at the fine print on the shelf label and figured out the cost by weight in his head. He explained to Alisha that the value price was a trick and that we should buy two of the smaller packets as originally planned. While they argued, I calculated the costs in my head and realized that Joseph was right. I was astounded: Joseph had been in a remedial math class at school since I had known him, and we often spent the whole hour of homework time doing multiple line addition and subtraction problems. But he had exactly the kind of critical math skills he needed to calculate costs on a severely limited amount of money.

In culturally sustaining pedagogy, teachers recognize the assets racially minoritized students bring to the classroom and use those assets to develop lessons that address and help students act with more agency given their lived experiences.

This story illustrates that children have critical thinking skills (which they may or may not learn from adults) that they use to navigate their life circumstances. An alternative approach to teaching is culturally sustaining pedagogy. In culturally sustaining pedagogy, teachers recognize the assets racially minoritized students bring to the classroom and use those assets to develop lessons that address and help students act with more agency given their lived experiences. Taking up this perspective is especially important when working with students who are understood by schools, parents, and teachers to lack the language skills needed for academic success and beyond. So, my goal from the time I first began my volunteer work and, later, teaching and research with Urban Pathways was to find an effective, culturally sustaining pedagogy to practice with the after-school students.

Though I received support for my research from Urban Pathways staff and parents, doing critical pedagogy with the students was not considered a priority in the after-school space because parents and instructors unwittingly sponsored deficit models of the students’ language and academic skills. To explain, even though parents and instructors had the same goals as I did, their version of critical pedagogy often got folded back into deficit perspectives, such as “giving” students language skills that they were presumed to lack. For instance, Victor, the Urban Pathways director, once asked me to design a math curriculum to help students learn how to budget money. The math lesson was certainly relevant in terms of core skills, but the life lesson was useless for the kind of sharp poverty the students and their families lived in: they had nothing to put aside. Moreover, as the story with Joseph and Alisha illustrates, students already had a sense of needing to save. The ability to save, to keep costly items like shoes and winter coats clean for future use by someone else if not themselves, and to only take what they needed and nothing more was essential to how students and their families lived in Southeast.

Had I followed Victor’s suggestion on the math lesson, I would have been teaching a mistargeted lesson that might have made the students feel irresponsible and at fault for being poor. Working from a culturally sustaining pedagogy instead would mean first taking note of students’ math skills, where they got them from and why, and developing appropriate lessons, such as cost calculations at the grocery store. Scaffolded lessons could have included helping students recognize how and why grocery stores try to convince people that they are getting deals when they really aren’t and if this is common across different store chains or even neighborhoods. Perhaps building even further into a learning unit, I could have helped students investigate predatorial corporate practices in urban neighborhoods and co-author a report or petition. For anyone who doubts that such a lesson is possible with children, note that Vivian Maria Vasquez, a critical pedagogue and former elementary school teacher, and her kindergarten class wrote stories about animal injustice, authored a petition, and wrote a letter to McDonald’s asking them to change gender-biased Happy Meal toys in the space of a year.

As a linguistic anthropologist who was also doing ethnographic research in the Urban Pathways after school program, I was not really focused on helping develop a critical math pedagogy; instead, I aimed to do this with language, using a framework called critical language pedagogy: a teaching method that is rooted in helping students recognize how power relations govern linguistic practices and norms. In other words, I intended to help teach the students how to navigate and respond to oppressive language ideologies that impacted their academic achievement and sense of self-worth. For example, even though the students understood that the language they spoke, which they called “slang” and which I, a formally trained linguist, called “African American Language,” was not really a broken language, they had internalized the racial stigma it carried of “ghetto” personhood and of less worth than the idealized “standard” language practices they were taught to take up. At first, my goal was to help empower the students by showing them the skills involved in code-switching, but I quickly realized that they were steps ahead of me not only in how they used language, but in how they thought about using it. By assuming students needed a deeper understanding of code-switching and designing a lesson around the hows and whys of switching, I was “language-splaining” to children who were intimately familiar with why they needed language flexibility. What I ought to have done was approach their work as already exemplifying these skills and knowledge of language. I did this much later, after the fact, when re-evaluating their work for my book on Black children’s language, as illustrated with the example below.

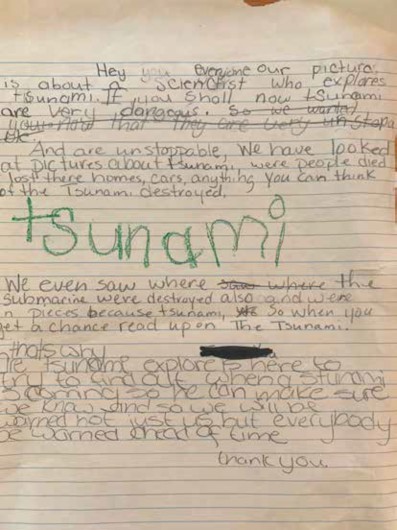

Here’s an example of my students’ linguistic sophistication. A group of fourth-grade students expressed concern about a major world disaster, the 2010 Haiti earthquake. They not only drew a scientist who was ameliorating the destruction caused by the tsunami that followed the earthquake, but they also decided to author a written report on the topic, shown in the photo I took of the report below. Following the photo, I have reproduced the report in typeface, reproducing all original text and formatting as closely as possible so that readers can follow my analysis (line numbers are mine):

[1] Hey you everyone our picture is about a scienctist who explores tsunami. If you shall now

[2] tsunami are very dangerous. So we wanted you now that they are very unstopable.

[3] And are unstoppable, we have looked at pictures about tsunami, were people died lost

[4] there homes, cars, anything you can think of the Tsunami destroyed.

[5] tsunami

[6] We even saw where saw where the submarine were destroyed also and were in pieces

[7] because tsunami, We So when you get a chance read upon The Tsunami.

[8] That’s why

[ ] 🡨(Thank You)

[9] Are tsunami explore is here to try to find out when a tsunami is coming so he can make

[10] sure we know and so we will be warned not just us but everybody be warned ahead of

[11] time.

[12] thank you.

To many readers, this text as reproduced signals the need for students to learn and use “academic language.” However, students are actually already oriented to the need to convince their audience of the importance of studying tsunamis by using an effective discourse style. But rather than use a singular writing style, such as informational, the students actually draw on multiple styles in order to argue their point. First, the students are aware that they needed to legitimate their knowledge, expertise, and arguments by detailing their observations. After a friendly greeting, the students begin with a thesis statement, arguing that tsunamis are very dangerous (line 2). To support this claim, the report explains that the scientists studied pictures of the tsunami’s aftermath and noted the loss of human lives and property that the disaster engendered (line 3–4). Following is more evidence of what the scientists observed, an appeal for others to research tsunamis, and a concluding argument about its importance: to try to warn others ahead of time, presumably so that people can prepare in advance to mitigate the disaster’s effects. Thus, the informational arc of the report follows a school-typical style of scientific reporting: thesis statement, evidence, conclusion, and future directions.

The authors of the report also appear to have attempted a friendly and accessible informational tone, perhaps to draw readers in and build sympathy for the people who had been affected by the disaster. The first line of the text, “Hey you everyone,” is corrected for formality and politeness, perhaps to soften the pointed aggressiveness implied in the initial construction, “Hey you.” Since the report had multiple authors, it is likely that this correction and the ones that follow are a result of students acting as co-authors. A general attempt at politeness, and also humility, is further suggested in the report’s closing, in which the authors thank readers. The students then draw on evidence and logic to construct a credible argument, but they also recognize the necessity of relating to a general public by balancing this form of authoritative discourse with friendly address terms and politeness. Finally, some of the corrections in the text convey an awareness of school-based prescriptive norms that govern spelling and grammar. The students, then, draw on multiple discourse styles to create a legitimate science report with a logical structure and accessible tone, whose credibility they know relies on academic writing conventions. As evidenced in their creative use of language, the students are aware that one needs to be both knowledgeable and approachable in convincing people to pay attention to important information and to act for the greater good.

The lesson for educators here is to look beyond what is normally considered writing errors or failures and to realize that students are in fact displaying their knowledge of how to use language to achieve a particular purpose.

In this example, the authors of “Tsunami” are quite literally acting as language architects. As sociolinguist Nelson Flores explains, a language architecture perspective allows us to see students as already engaged in the kinds of language work teachers and school institutions are asking them to do. Flores notes further, “From this perspective… [Common Core and other] state standards are not demanding mastery over academic language, but rather are calling for students to be language architects who are able to manipulate language for specific purposes.” The lesson for educators here is to look beyond what is normally considered writing errors or failures and to realize that students are in fact displaying their knowledge of how to use language to achieve a particular purpose.

My experiences of trying and failing to “empower” students in a way they didn’t need taught me that a successful critical pedagogy recognizes the language architecture strategies students use and centers them in teaching, even when these strategies conflict with the educator’s notions of how to best support students in the classroom. I believe that the first step to resolving such conflicts is for teachers to have the confidence and humility to position themselves as learners in such instances. Teachers could try to recognize when students are attempting to advocate for themselves in how they use language instead of writing them off as being resistant or difficult.

Furthermore, it bears mentioning that my position as a teacher was constrained not just by ideology, but also by the circumstances and contexts in which I was asked to produce measurable results for students’ language and literacy learning. In this role, I had to show evidence that students were prepared for the standardized, high-stakes tests they took at school in order for the after-school program to continue to receive federal and local sources of funding. I was afraid that if I did not use traditional learning formats, no one would take seriously my efforts or those of the students. I was more concerned with assimilating their cultural interests into these methods rather than drawing from what they already were doing and letting them self-direct more independently within learning activities. Looking back, I believe that as a teacher, I often fell into the trap of focusing too much on how my work would be institutionally evaluated rather than how it would benefit the students. Now, I would trust what other practitioners have shown: that prioritizing student learning tends to produce positive results regardless of the particular standards put in place that measure what counts as learning in the first place.

A key part of a critical pedagogical perspective involves stepping back and letting students articulate their own positionality and learning interests in the classroom rather than defining those for them.

There are three lessons I took away from my experiences teaching and researching with Alisha, Joseph, and the other after-school students. First, students come to the classroom as critical thinkers with their own ideas about learning and social justice. It is important for educators to learn what those are, sponsor them, and let students help design activities and lessons. Second, promoting rigid notions of difference—racial, cultural, or otherwise—does not serve students or recognize their efforts to engage in learning. Even with the tools of expert observation and analysis, it is often easy to assume that there is a mismatch or clash in the classroom between the so-called “dominant” and “minority” cultures. Here, I am speaking specifically to well-intentioned liberals and progressives who may or may not be aware that there is a tendency to reinforce difference by positioning oneself as a “(white) savior,” or a white person who saves Brown and Black people from what is perceived as the toxic elements of their differing cultural practices. It is essential for teachers to be able to identify and support how students make school-based language and literacy practices their own, even if these practices do not appear to benefit them on the surface. Third and finally, assuming it is an educator’s job to teach students what oppression is and how to act against it reproduces deficit thinking. A key part of a critical pedagogical perspective involves stepping back and letting students articulate their own positionality and learning interests in the classroom rather than defining those for them. Educators, in other words, should seek to co-construct learning and critical consciousness with students rather than impose it upon them.

Suvanni Oates

Suvanni Oates