“What are you eating?” “What’s in your lunchbox?”

Language works in many ways. Sometimes when you ask somebody a question, you really want to hear their answer. Other times, you ask somebody a question to criticize. So, when a teacher asks a student a question about their lunch, it can be a way to discipline the student to conform to cultural norms about food. In fact, talking about food often has an evaluative dimension. This includes both when you ask questions and when you characterize food explicitly. Moreover, conversations about food reveal our judgments of other people. So “healthy”, “unhealthy”, “delicious”, “gross” or even “good” food and “bad” food can show our understandings of people, and negative language about food can have negative social and psychological effects, such as marginalizing people.

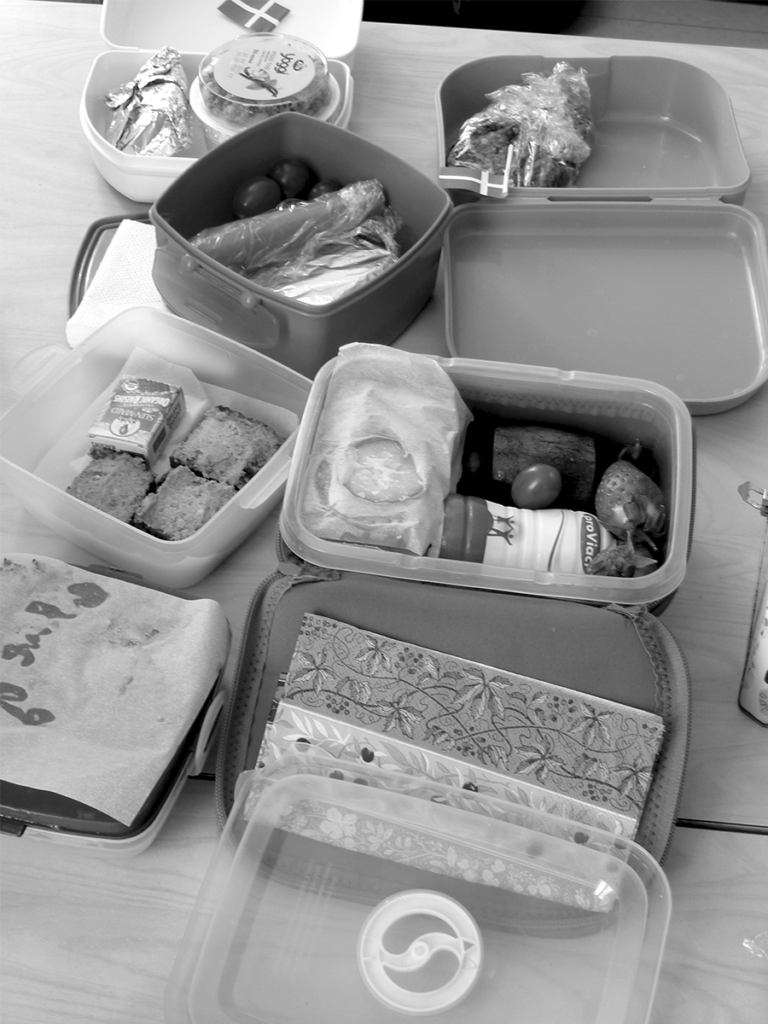

I spent two years participating in and observing the daily life of a class of primary school children (5–7 years old) in Copenhagen, Denmark, in the 2010s. One thing I observed over and over was that teachers requested that children bring Danish-style rye bread (more on this below) rather than white bread for their lunch. Rye bread was talked about as “healthy,” especially compared to white bread, which was labeled as “unhealthy.” I also saw how the two (white, middle-class, ethnically Danish, female) teachers often singled out children of minority backgrounds (mostly children of African, Middle Eastern, or Asian descent) as targets for promoting their understandings of proper food using linguistic strategies to make the children comply with the classroom norms. This included asking children what was in their lunchboxes each day.

My study was part of a larger project in an urban Danish public school that was characterized by an ethnically, religiously, and socially diverse student population. The children in the class I followed had Danish, Chinese, Icelandic, Syrian, Somali, Pakistani, Iraqi, Turkish, Turkish-Kurdish, and Moroccan backgrounds. As part of my ethnographic research, I spent many hours with this class. I went with them on field trips to the countryside, to the theater and museums, stayed with them in the schoolyard during breaks, hung out with them at the library, and participated during regular class time sitting on a low stool at a desk next to the children. I also ate my lunch with them. I talked to their parents at home and interviewed the teachers. I took notes about what happened, and I video and/or audio recorded in almost every class, resulting in more than 300 hours of recordings, some of which I have transcribed in detail. Recordings guarantee that you catch the exact wordings in a situation, and this offers insight into the ways everyday life unfolds through language, how meanings are constructed, and how people are assigned identities.

Now, you may think that “healthy” food is always good, that it is an objective category, and free of personal or cultural bias. However, what “healthy” means varies greatly across different cultures.

I never expected kids’ lunchboxes to become such an important part of being labeled a successful or unsuccessful student. The children I worked with, like most children in Denmark, brought lunch from home, and because I too am Danish, lunchboxes were a familiar thing to me, as was the overall school context. But I was surprised that in the class where I worked, having a “healthy” lunch was so much more important than it used to be when I was a child. This was probably a result of more general developments, such as growing attention to health and to child obesity and a diversifying population. These days, being a successful and well-accepted student includes understanding a “proper, healthy” Danish lunch. There is no simple answer to why this is the case, but I know that the school principal instructed the teachers to focus on health. He was aware that many students did not get breakfast at home and that there were issues regarding healthy eating practices in some families. In addition, he knew that middle-class parents viewed health as an important issue. Both to help the less privileged students and to attract more middle-class families, he wanted the school to have a health education strategy. The teachers, however, had not been told how to carry out this strategy. They were not trained to handle the diversity of food cultures in the classroom, nor were they attentive to any side effects of their words on students. All the students’ parents provided their children with lunch, but some parents had different understandings than the teachers of what a good lunch should include, in particular whether it needed to include rye bread. This is to be expected, as Danish-style rye bread is a culturally specific thing and not universally known or acknowledged as a marker of healthy food.

Danish rye bread has a 1000-year history, and today it is the classical, traditional lunchtime staple for both adults and children, eaten with different toppings. Danish rye bread is made of sourdough, rye flour, salt, water, and rye kernels. Loaves are baked for hours and end up dense, dark, and bittersweet, containing lots of fiber and little fat. Nutritional experts agree that this rye bread is extremely healthy, and Danish pediatricians recommend children learn to eat it, so Danish children are served rye bread until they come to appreciate it—or at least until they eat it.

So, back to the classroom. As rye bread is particular to Denmark (as well as to Finland, Northern Germany, and a few other places), I was not surprised that parents from non-Danish backgrounds did not necessarily include it in their children’s lunch. They often gave children “white” bread, i.e. wheat-based breads (including pita bread, toast, and white rolls, etc.), to eat. From the perspective of the teachers, these children were not observing school norms, and the teachers wanted to teach them how to conform. During the first months of the school year, they asked all children daily what they had brought for lunch. They used this time to talk about the wonders of rye bread, and they also made it clear that the children were not supposed to eat “white” bread. Further into the school year, they only asked about the children’s lunchbox contents if they did not expect them to have brought rye bread. In that case, they would repeat a question like, “What’s in your lunchbox?” or “Why don’t you eat your rye bread?” day after day. These questions were an implicit criticism, which would become explicit if it turned out that the child, in fact, had no rye bread. The child was then criticized for the food and told to remember to bring rye bread. The teachers hoped that this experience would make the children go home and tell their parents that they needed something other than “unhealthy” white bread. Over the year, difficulties escalated as teachers became increasingly frustrated that some—immigrant—children continued to bring the “wrong” kind of food.

Now, you may think that “healthy” food is always good, that it is an objective category, and free of personal or cultural bias. However, what “healthy” means varies greatly across different cultures. Furthermore, when parents and teachers disagree on what makes a good lunch, kids may get stuck in the middle. Take Fadime, a student from a Turkish-Kurdish background, for instance. She rarely brought rye bread to school, even though she was very aware of her teachers’ expectations. One day at lunch when she found that her mother had given her a white roll with cheese in her lunchbox, she hid it under the table when eating. This immediately drew the teacher, Louise’s, attention to her. Louise asked Fadime, “Why don’t you have rye bread?” Louise knew Fadime was not responsible for the food she brought to school, and Louise was not actually looking for an explanation. Fadime was only six years old and not capable of accounting for the contents of her lunchbox. What Louise really did was perform a reprimand through that question, which could be reformulated as, “You’re bad for not bringing in rye bread. Be ashamed now and act differently (i.e. bring rye bread) tomorrow.” And Fadime clearly was ashamed, as she was hiding her food and excusing herself: “We did not have any rye bread,” “I don’t like rye bread,” and pointing to another girl at the table, “Amira also brought a roll.” Louise ignored all of this and began to inspect the rest of Fadime’s lunchbox before exclaiming, “That is really unhealthy, Fadime. You’re kidding me!” Then she asked for Fadime to bring her report book and wrote a message to Fadime’s parents— and although I never read it, I am very certain she was saying something about the norms of school lunch and the healthiness of rye bread. To Fadime, healthiness was not as relevant as the difficult situation she was put in by the adults around her, and this example shows how the way that food is talked about can influence the position and feelings of a child in class.

Teachers want their students to make healthy choices, and from one perspective, that’s a great goal. But when teachers put a lot of emphasis on the superiority of some food over others, it ends up marginalizing students whose food is different.

We’ve all had the experience of eating lunch surrounded by our classmates, so we understand how vulnerable that can feel. Having your lunchbox criticized by a teacher or other kids might make you feel like you don’t fit in, and that may affect how you feel about yourself as a student in general. Teachers want their students to make healthy choices, and from one perspective, that’s a great goal. But when teachers put a lot of emphasis on the superiority of some food over others, it ends up marginalizing students whose food is different. Situations like this occurred daily not only to Fadime but also to several of her classmates, all from minority and immigrant backgrounds. These children were treated as belonging to families with irresponsible parents and misguided understandings of health, and they struggled with understanding what was wrong with their food – and what was wrong with them. Of course, the teachers did not intend to hurt these children. However, they tried to accomplish their aim of making students eat a particular type of “healthy” food in an unnuanced way, and it had harmful consequences. In conclusion, to me it is obvious that schools should give all children a fair educational chance by making them feel included regardless of what they eat for lunch. Notwithstanding the more objective health qualities of foods, it is an open question whether it is necessary or even a good idea for teachers to focus on health It may create an unsafe learning environment and have long-term negative effects in relation to children’s potential to feel and be successful in school, thus reproducing social and educational inequalities. In the case presented, minority children suffered, when they actually needed a supportive environment.